Sorry, this entry is only available in Nederlands.

Author: Oscar

Fragmented – Mary Janssen

Keramiek – Dolyn Kuiper

The White Sand in Exile – Xuan Ha (Danang, Vietnam)

Xuan Ha closely approached the business of extracting and mining white sand in her hometown (Thang Binh, Quang Nam) – where the glass is produced to export to developed countries. Xuan Ha reflected on the impact of the business, which is led by large companies, on the physical and emotional wellbeing of the locals. Wandering along the coast she picked up the glass bottles that drifted to the shore from various directions, as if they were returning home to their source; the sand they were made from. Overexploitation spreads across the seaside communes. The communes are built on sand, planted on sand and buried under sand and yet their land is being exported away from under their feet. The sand is a nonrenewable natural resource. Once taken it can not be replaced.

The idea “The White Sand In Exile” originates from the culture of the people that live in the Central. They use the sand to make a small white pile to burn the incense on the house altar. It is believed that the sand is a spiritual door between both worlds of the living and the deceased.

Ferengi at De Parade!

This summer at theatre festival De Parade:

Ferengi (Stranger)

A mobile dance/theatre performance in which you participate yourself.

Beautiful, moving, soothing and disturbing at the same time.

“People think they’re fantastic! But what happens when we meet strange characters who are much more fantastic than us? What shall we do with those strangers? Vaccinate? Isolate? Capture?

But what do we do when they can do everything so much better than us that they have seen through us in a split second? Is that really bad?

Put on your safety suit and let yourself be taken into this incorporation ritual of the Ferengi’s.”

15 July until 23 July in The Hague

29 August until 03 September in Amsterdam

Creator/director: Dienke Groenhout

Dansers: Alegría van Poppel Lubeigt, Anand Dhanakoti, Fiammetta Ruggiero & Maria Sava

Technique: Oscar Meijer

Sound design: Remco de Kluizenaar

Ferengi performance Kunsthal Rotterdam

Het woord

Laatst viel er opeens een woord in verband met mijn werk. Ik had een voorstel gestuurd naar een groot festival in Nederland en in het antwoord stond het genoemd.

Er werd nog net niet gezegd dat mijn werk ‘het was’, maar laten we zeggen, het woord viel letterlijk. Het woord was culturele toe-eigening.

Er dook een enorm groot aantal vragen bij me op:

Wat had ik mij precies toegeëigend dat blijkbaar niet ‘rechtmatig’ van mij was?

En wie bepaalt er dan wat wel rechtmatig ‘van mij’ is?

Werd ik nu gecategoriseerd in een bepaalde groep die mijn cultuur is/zou moeten zijn?

Heb ik überhaupt een cultuur waar ik toe behoor?

Het hele project Ferengi is juist bedoeld om mij en iedere drager van een alles verhullend kostuum los te maken van zijn of haar context of geschiedenis, en een heel ander iets te zijn waar nog geen categorie voor is.

Maar in de ogen van iemand (die het woord had gebruikt) riep dit project ideeën op over culturele toe-eigening.

Ik zocht het woord op. Er stond een redelijk summier stukje tekst op Wikipedia met als voorbeeld de hoofdtooi van een indiaan bij een carnavalsfeestje.

Hmmm, daar kon ik niet zo veel mee.

Het woord toe-eigening impliceert dat er zoiets bestaat als cultureel bezit.

En bezit kun je stelen omdat (de meeste) mensen niet de gewoonte hebben om bezit te delen.

Maar is cultuur niet juist iets om wél te delen? Cultuur fuctioneert toch helemaal niet als je het voor jezelf houdt?

Maar veel meer nog: er was iemand die een aanname deed over wat of wie ik was (ik had geen foto van mezelf meegestuurd) en vervolgens vond dat, passend bij mijn kleur, leeftijd of sekse, er een bepaald cultureel speelveldje voor mij is neergelegd dat ik mag vertegenwoordigen.

En ik vraag mij af, wat is mijn culturele speelveldje dat de woordzegger voor ogen had?

Ik bedoel, hebben we het over pannenkoeken, molentjes en tulpen?

Wat mag ik in de woordzeggers ogen representeren?

En hoe kan ik dit in overeenstemming brengen met mijn eigen waarden?

Is het afbakenen van mijn speelveld waarin ik me mag bewegen en het mij toewijzen van bepaalde dingen, en mij verwijten dat ik anderen dingen afneem die niet van mij zijn, niet juist precies dat wat de woordgebruiker niet wil dat haar/hem geschiedt?

En is het niet een vorm van polariseren en buitensluiten?

Mij gaf het mij in elk geval onmiddellijk het gevoel dat we tegenover elkaar staan, in plaats van dat we iets delen.

Nicolas Bourriaud zegt dat etniciteit niet hetzelfde is als afkomst, en hij bepleit dat cultuur moet worden gedeeld, verspild, en dat er royaal en vrijgevig mee om moet worden gegaan als wij daadwerkelijk diversiteit willen bereiken.

En ik merk dat ik het met hem eens ben.

Ik kan niet alles maken. En ik ben blij dat zoveel mensen ook hun dingen maken, en als ik dan mijn ding maak, dan kunnen we samen dat hele palet maken van alles dat gemaakt wil worden.

Performance Centre Pompidou Paris

In January 2023, Dienke Groenhout performed with a number of her ‘Ferengi’ costumes at the Center Pompidou in Paris in the series ‘Uninvited’.

Soil Sealing – Sadra Wedjani (Iran / Germany)

The inner and the outer

Our first item of clothing is our skin. The body we are in. We cannot choose a color or a shape. Your skin, your body, your first suit already contains so much information and carries so much history with it and that affects your identity even before you have put on any piece of clothing.

(Work in progress: The inner, an inside-out costume consisting of organs made of textile)

(Work in progress: The inner, an inside-out costume consisting of organs made of textile)

Then follow the next layers with which you can influence that identity somewhat. As a person you always carry a context with you. If we could see that context as a piece of clothing, an extension of our body and we were able to wear it, what woud it look like? What would I wear?

When I travel I think about what makes me a stranger when I’m somewhere else, why the rules are suddenly different for me or don’t apply.

It can bring freedom. But sometimes it is too tight a framework.

For example, if you’ve been living somewhere for three months and people are still shouting “Welcome to my country!” then you suddenly feel a little less welcome, and you wonder when you are aloowed to become one of them.

While I visited Ethiopia in 2019 I started to wonder how I could wear my own context. Like a piece of clothing. Maybe I could make sure that people no longer had a reference and no starting point to compare me with anything.

How will they then approach that stranger?

I made a package or costume out of banana leaf and bamboo and grass that could completely cover me so that nothing of my own self was visible.

I walked down the street in it.

At first it felt safe inside the suit. Nobody saw me. Nobody knew what or who I was. I didn’t have to smile or to answer to anyone. But at some point I started to feel a little lonely. People made a lot of contact with me, but it wasn’t really me. I couldn’t see them and they couldn’t see me, at least not ‘really’. They made contact with my outside. I noticed that I wanted to reveal myself in order to make real contact and that I also wanted to own some parts of my supposed identity.

But I also noticed, because I became disconnected from people, that I didn’t actually show anything of myself. It wasn’t me who did the performance, it wasn’t me who was on ‘the stage’. It was the audience who responded to me, who did the real performance. They began to reveal themselves through my concealment.

Some people made a cross to ward of evil, others thought the suit was very beautiful and wanted to touch it. Some people thought it was a forgotten Ethiopian tradition. Some people were happy about it and others commented on how much bread you could have made from all that banana leaf.

The costume revealed the fear, pleasure, curiosity, practicality, misunderstanding, and sense of beauty in the people themselves.

Perhaps when people recognize little to refer to, they directly create their own individual context for something.

That says more about themselves than about the others.

Since then I have made more costumes (three of which are currently on display at Musuem Villa Mondriaan). The costumes are more than just a shell, they are an exploration of possible identities.

Which part is coincidence, which part is allocated and which part is a personal achievement?

Identities reside in a symbolic time and space in an imaginary geography. They are fictional, so to speak. Made up by a group, by an entire society or a political idea.

“Wearing” a stranger is a truly transformative activity. Although you are being watched yourself, you are secretly spying on your audience.

Rollie Bollie

This costume was introduced in the previous newsletter in the blog “stuff stuff stuff”. Nothing was bought for this ‘costume’. It is too heavy to walk with and thus it tells its own story. All the things we collect, all the stories from the past, memories, souvenirs are incorporated into it. They are precious materialized thoughts and sentiments until they become ballast. The ballast of a life became its own entity.

AAAAAAH! – Hanna Speelman

Hanna Speelman 15 May till 15 July

Illustrator Hanna Speelman likes to approach political themes with a humorous undertone in her work. In doing so, she uses different techniques. For this exhibition she makes a series of 40 masks called AAAAAAAH!

The Masks depict the different faces of fictional and non-fictional monsters and how people give a face to ‘fear’ through the ages.

Ferengi (stranger)

From the 5th of March until the 19th of September the exhibition Ferengi is showing in Museum Villa Mondriaan.

You can visit the project “Ferengi” (Stranger) the first few weeks online and hopefully from April in a live visit!

The exhibition is showing costumes in a broad sense of the word, meaning: you can wear them but they are much more than just a decorative function for the body.

They communicate the identity of their makers. Dienke Groenhout, the initiator of this project, made three of the costumes. The other costumes are made by Tamrat Gezahegne from Ethiopia, Gígja Reynisdóttir from Iceland and Valerie Asiimwe Amani from Tanzania, all artists that Groenhout met during her travels. Videos of the performances in which the costumes are being worn provide insight into the functioning of the costume as an extension of the identity.

The artists wonder what an identity actually is, which part of it is just a coincidence, which part is allocated and which part is a personal achievement. According to the Ferengi project, identities are located in a symbolic time and space in an imaginary geography. Fictional, so to speak. Partly by oneself and to a large extent by a group, an entire society or a political idea.

Please also visit the site of Museum Villa Mondriaan.

Shades of discomfort – Gigja Reynisdottir (Iceland)

On display from January 16 to March 16, the work “Shades of discomfort” by Gigja Reynisdottir.

This orchid, which Gigja made especially for “Het Raam”, is a flower in the ‘Homo Botanicus’ series. Gigja interweaves natural shapes and vegetation, with her wonder at the human condition.

The human flowers express the physical and psychological experience of being human and the complexity of human emotions, relationships and society.

The Orchid, a worshiped flower, but nevertheless a parasite that feeds on other plants, symbolizes how our consumer society is organized.

We don’t really ‘see’ what we are buying.

Come and see that flower!

furthermore…

STUFFSTUFFSTUFFSTUFFSTUFFSTUFFSTUFF

As an artist you are mostly preoccupied with stuff all the time. If you take artistry very physically, you actually see things moving around all the time. It’s a lot of dragging.

The third costume I’m making for the ‘Ferengi’ exhibition has everything to do with all that stuff that just keeps sticking to me. Some things for years. Some even belonged to a grandmother or grandfather… Really almost everyone has too much stuff.

In the book ‘Are we human?’ about design, it says that the one thing that distinguishes humans from animals is that they design and produce an infinite stream of things. With all that design, they finally also redesign their own behaviour and that makes humans the only species who, with all the necessary design that has been devised for their facilitated survival, ultimately also makes that same survival less and less likely. In other words, humans design their own demise and look at it with a strange mixture of pride and horror.

“Oh dear!” I thought, “how do I relate to this as an artist? I am a nest polluter! Maybe worse than many others!” I am pre-eminently busy putting my thoughts on the world in a physical form. Thoughts sprout from my mind made of wood, and rope and plastic and stuff and paint, objects of considerable size!

These things in their specific composition have indeed been spirited with an idea and a meaning, put into them by me and by the public, but once the work of art has done its job, I cannot deny that a lot of material is left meaningless.

The value of the material can suddenly be lost when the artwork is finished.

That is why I thought that for that third costume I could only recycle previous artworks and possibly use things that I already possessed and that had accidentally stuck to me while traveling or elsewhere.

It wanted it to become a kind of collected ‘thought cloud’ that shows how thoughts and ideas become a form of material.

Slightly round or convex. A Rolliebollie.

In my head that became the working title of the collection sphere.

In Namibia they call the dung beetle a rolliebollie. Nice word.

I wondered if there was any other similarity between the beetle’s dung ball and my work, other than the round shape and the fact that I felt like I was dragging around a lot of shit. Why does a dung beetle actually collect dung? I looked up a few things about the dung beetle. The beetle eats the dung, but also appears to be an important player in the field of diversity. Besides moving about 100 kilos of soil per year, a beetle also spreads a lot of seeds.

Perhaps you could say that an artist, and even more so a traveling artist, does the same for culture, providing diversity?

In addition, the Egyptians worshipped the scarab beetle as a sacred creature because the Egyptians believed that the beetle recreated itself over and over again. The beetle does indeed lay an egg in a rolliebollie from which a new beetle emerges. The dung beetle was therefore given the initials XPR in the hieroglyphs, where the X stands for origination, the P for creating and the R for transforming.

I may not eat things, but as an artist I do need them as ‘food’ for ideas.

I transform stuff, I could say…

Seen in this way, I actually think the above text on the bag is a compliment.

Yippee! I am a dung beetle!

Workshop/Artist Talk

“Defining ourselves through otherness”

On Saturday July 18th and Sunday July 19th, from 13:30 till 16:00 in de Maakfabriek, Churchillweg 21, Wageningen

A workshop in which you recheck your values and identity, and create new symbols for yourself. The workshop is a joint collaboration between Tamrat Gezahegne (multimedia artist) and Dienke Groenhout (interdisciplinairy artist).

Tamrat: “I can say I am Ethiopian, it is in my passport and it is an identity that was given to me, but can I truly represent it? I don’t even know what it means to say I am Ethiopian.

So I traveled my country to find out about it, and to find out which values I share with all the nationalities that Ethiopia contains. Each symbol is like a talisman. The script includes traditional and modern habits, food cultures, heritage and social values.”

Dienke: “I traveled the world a lot and I was given many names like foreigner, outsider, stranger. At a certain point I felt that my outside was disconnected from what I felt I was on the inside. People thought that I belonged to some group that I didn’t represent in my own feelings. And I started to research this feeling by making costumes for myself that created a whole new context for me. A possibilty to represent a new identity that I could be and to wonder what I wanted to be.”

The costumes Dienke makes and the symbolic script that Tamrat designed where born from similar research questions: can we try to redesign the values that we find important in life, and ask ourselves ‘what do we (want to) represent in this world?’

Workshop:

Artist talk about Tamrat’s new script named Wehed, which means mixed in harmony.

Artist talk about the “Ferengi” project that Dienke did in Ethiopia.

After the presentation you can design your own symbols and blockprint them on a small flag (or tattoo it on your body). We will create a flagline with our joint values from the group and display it in the new exhibtion window of MakeFactory.

Ferengi

When we arive to new places we try to connect immediately to what we know. We try to give the strange a familiarity. Do we need a similarity to connect? While I traveled many continents I was always categorized immediately and given many names even though I was there for the first time. I wondered what will happen when there is no category for me yet and no context to refer to? How do people face the strange? The suit was made with the help of Gennet Hussein, presented at Guramayne Art Centre and now in possession of The National Theatre, Addis Abeba.

Floating Home

“Staying is not the same as coming back”

“How did we get here?” was the theme of this international exhibition. The question aimed to acdress our identity seen in a global perspective. MakeFactory created the performance installation ‘Floating home’. A landscape of paper furniture that seems to have fallen apart. People can enter the deranged room that invites them to a moment of reflection. Voices are whispering questions to wonder about. In cooperation with the dancers of Muda Africa, who created a special performance for this work. Sponsored by Safmarine.

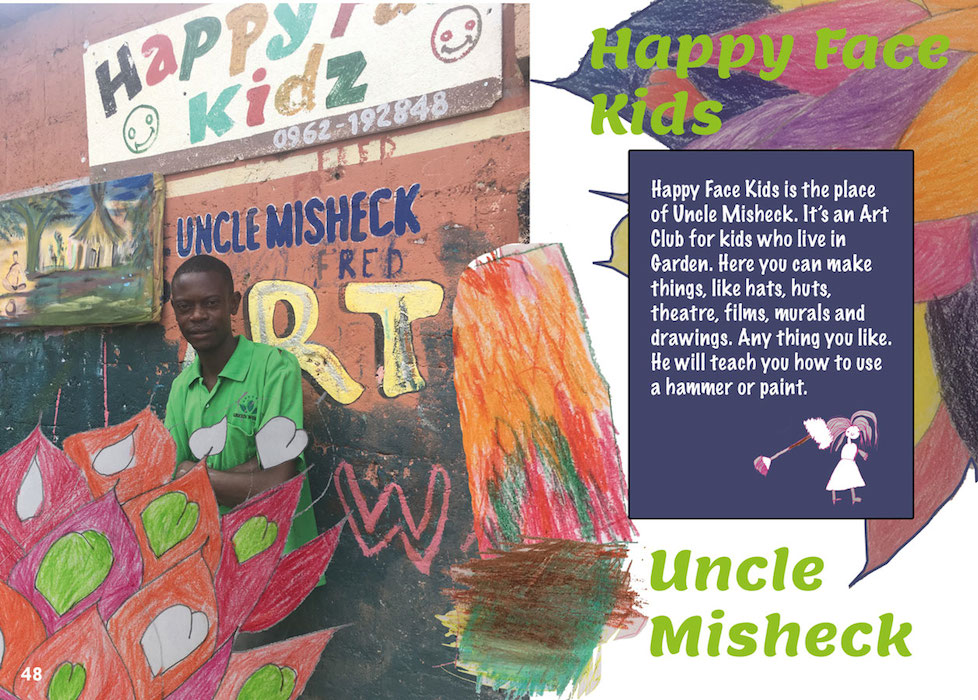

Garden Stories

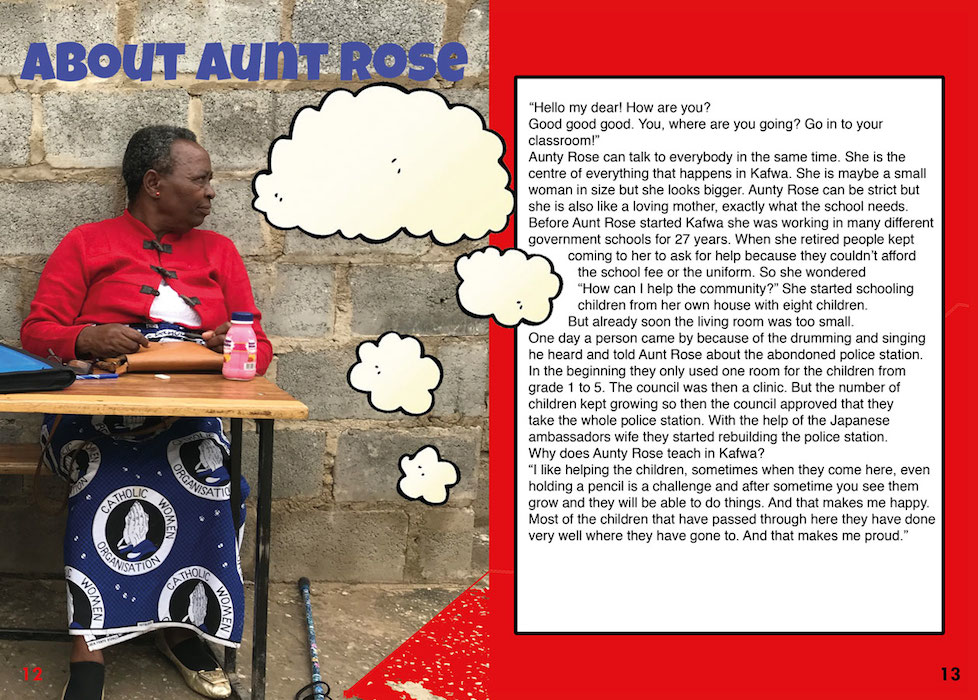

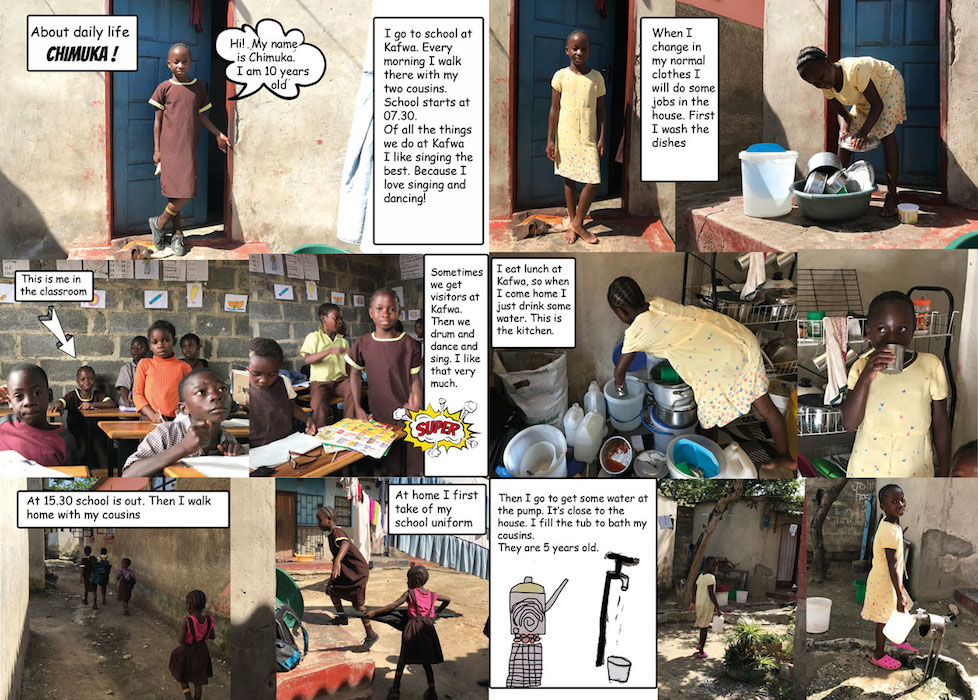

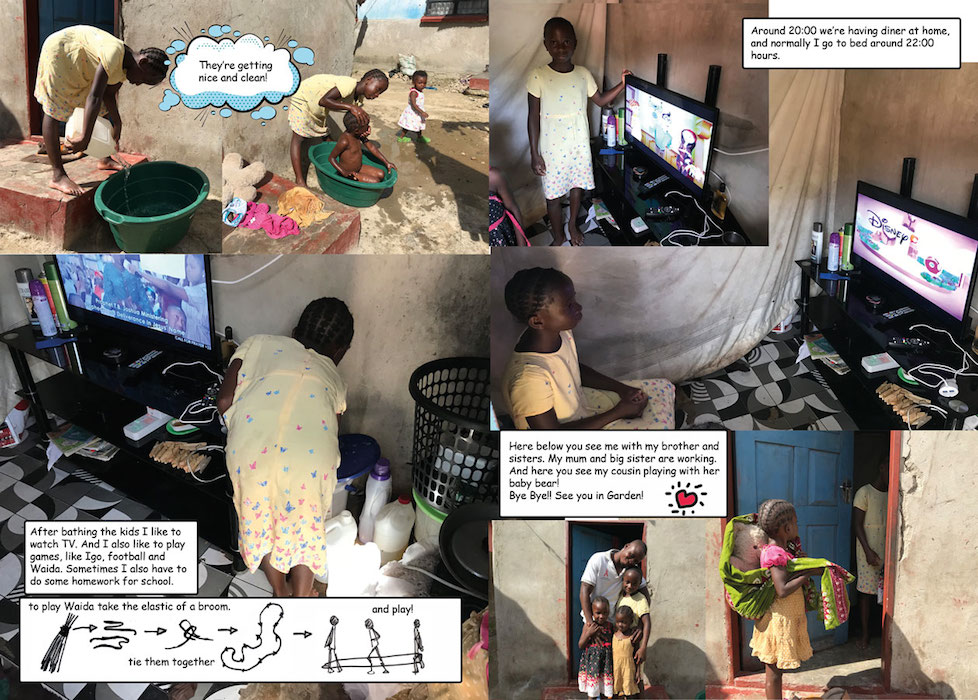

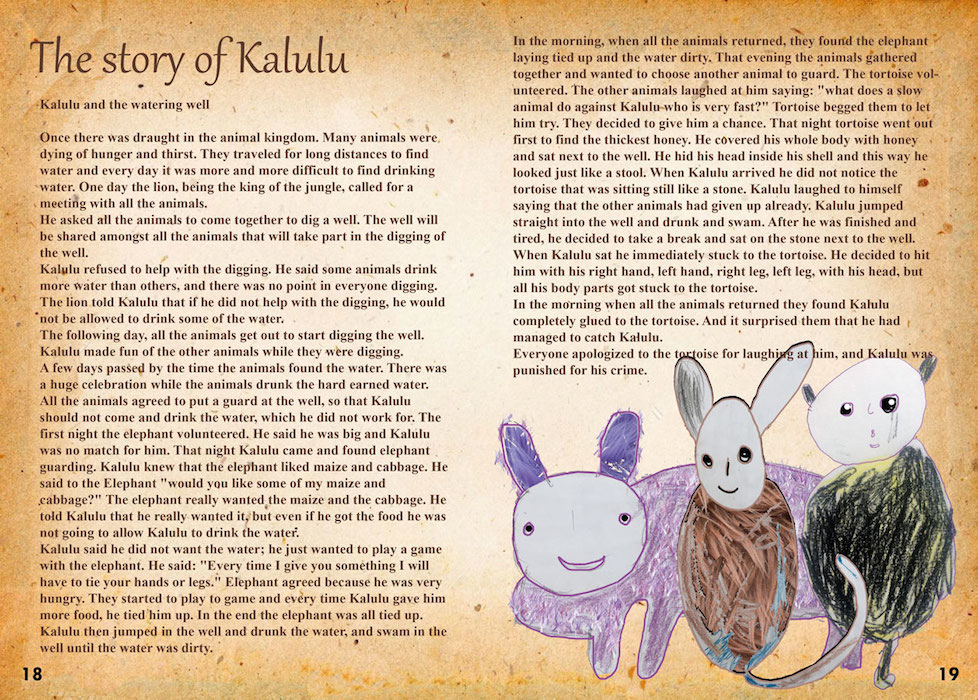

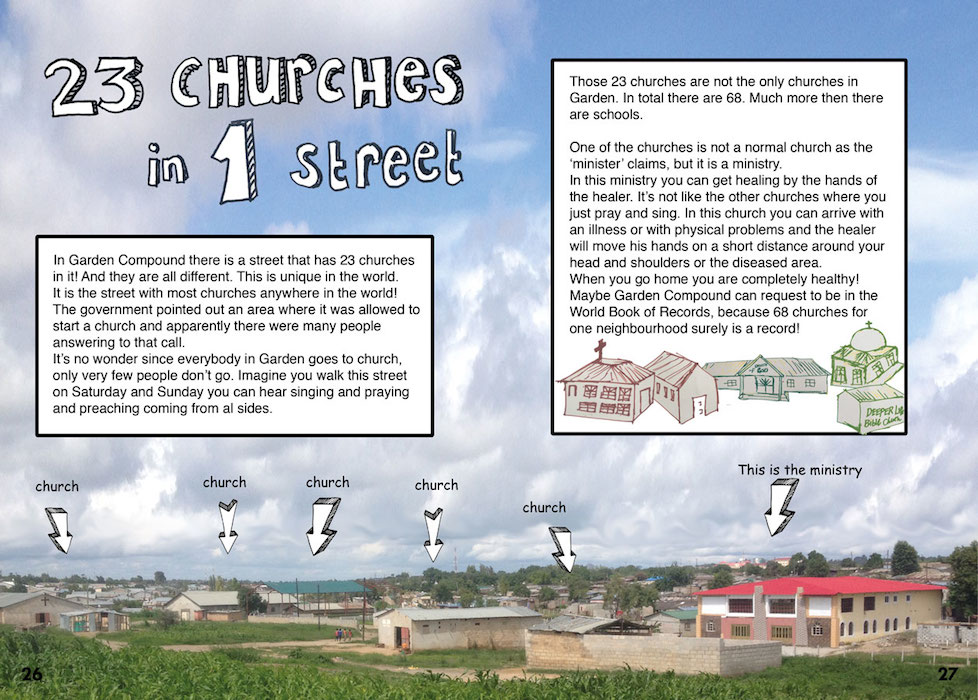

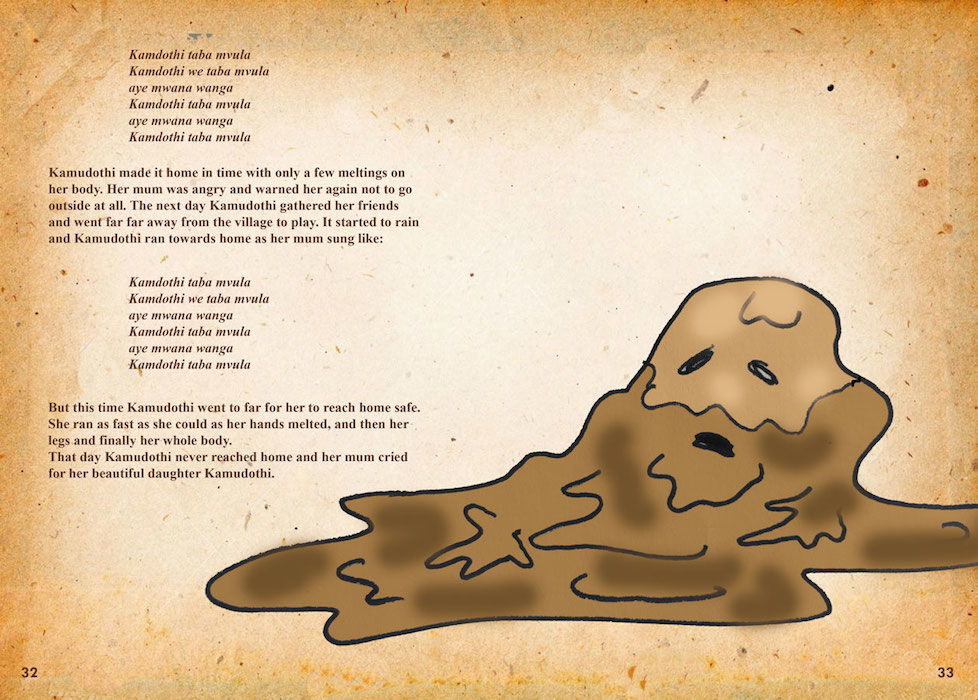

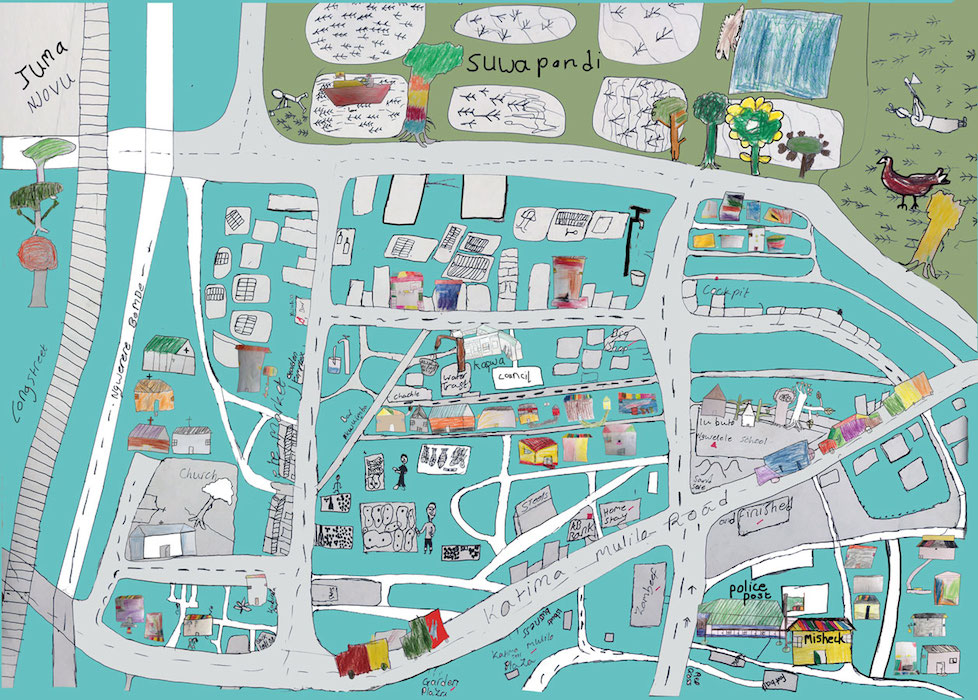

In cooperation with the theatre group Barefeet Theatre, whose core business is making theatre with street kids and vulnerable youth, MakeFactory made this magazine-like book. Zambia has more then 70 spoken languages. To be able to understand each other, the Zambian government has decided for English to be the official language. Of course language transfers culture more then we are aware of. The Zambian youth cannot relate to the English stories in the nearby library. Therefore Barefeet and MakeFactory thought it urgent to give local life and local people a stage and a place in the library. The book contains local history, urban legends and traditional stories from the neighbourhood Garden Compound. The editorial team was formed by youth from the hood, and an art and drawing team was formed by the children of Kafwa Drop In Centre and the art group of the library.

View here the entire book.

Pecheur de Plastic

2019 Centre culturel Le Chateau

Saint Louis, Senegal

Pecheur de Plastic was a participative performance connecting the fishermen’s traditional rituals of hauling in the nets to modern dance. The dancing school le Chateau culturel in St Louis is situated in the middle of the fishermen’s quarter on a peninsula that is slowly being eaten on one side by the sea and on the other, the river side, by enormous amounts of plastic pollution. The performance was participatory. In invited the public to join in the movements of the dance and to collect plastics together with the dancers while they carried the nets through the streets.

Some gorgeous pictures made by Abdoulaye Toure in sequence of the performance:

State of the art

Half a year after we have returned from our foreign productions and adventures, it is still adapting to Dutch life.

When you live a life on the road you are always an exception and there are far fewer rules for a traveler than for someone who is permanently located somewhere. So much is suddenly possible when everyone knows that you will be gone soon!

Back in the Netherlands, the system, to which even the art world is subject, suddenly becomes very clear.

There is an extraordinary number of rules in the Netherlands. For example, dogs are not allowed to walk for themselves. How strange it seems, if you have been in 8 countries for a year where the dogs move freely between people, to see them walking on lines.

Most rules are all meant to protect us and take care of us. We have many rights. If something goes wrong, a new rule will be added immediately.

People get sleepy, but also grumpy, and complaining.

After all, what can we bring in for ourselves in this neatly arranged life? What can we do our very best for? Everyone seems to be looking for meaning. What do we do all this for?

Art seems to be able play a role in this whole, but what is that role?

In a plea for the autonomy of the arts, Jeroen Boomgaard (Open 2006) says that art in society has the role of our conscience, of reflection and of the representation of things that seem to be forgotten in a world focused mainly on functionality and efficiency.

But there is also a pitfall. The government is also aware of this. She knows that art can be used in that way. And therefore asks that the arts be used more and more efficiently.

For the use of something. Artists can receive subsidies for solving problems related to loneliness, for example, or for innovative ideas that we can then apply in a very practical way.

But with that, art loses its autonomy. Autonomous arts no longer exist at art academies as a study direction. Stripping the autonomy away from art also takes away the power that art has. It is made dependent and can therefore also be held liable for an alleged failure. Useful art can no longer function as a conscience. In a society that seems to have sacrificed most of its values for unimpeded economic market progress, the autonomy of the arts could offer an alternative. (Open 2006)

After having made several visits to the Dutch embassies in the various countries that we visited, it becomes even clearer how much the Netherlands is focused on the market economy, a dominant pivot that is never under discussion itself.

The arts must be useful to society! That is the trend. If it does not yield a lot of money or an extraordinary status, then Dutch art abroad is not a cost for the government.

In Africa, the Dutch embassies are always in the smallest building, preferably shared with Europe or something, because on that continent, there is nothing (more) for them to get. You can get a subsidy to set up a lucrative beer factory, but there is no money for arts and culture.

Why would you invest in someone else’s society if you don’t get anything in return?

Well … I don’t know the answer, but the French, the Belgians, the Norwegians and the Swedish do it.

Arriving here in the Netherlands again, it appears that an investigation has been demanded by the national government concerning work regulation on behalf of the Ministry of Social Affairs.

Hans Borstlap, head of the investigative committee, concludes that there are too many self-employed people in the Netherlands who could actually be employed by large companies.

I remember a while ago that Jet Bussemaker declared, as the then sitting Minister of Education and Culture, that artists should receive ‘normal’ wages just like everyone else.

Yeah!!! called all the artists. Not realizing that what was actually said was this: “There is less subsidy for the arts and the arts need to be used even more usefull for the public good, because we want to pay for usefulness, and not for art itself.”

Does this art system still work?

Anyway, now the work regulation committee of Hans Borstlap has proposed that all self-employed persons should be employed, unless …

This means that all artists and dancers and theater makers and all kinds of other makers are obliged to demonstrate that they are unable or unwilling to work for companies or that there is no one who can or will hire them.

I thought to myself that I actually don’t mind being employed. Certainly if I can continue to do the great work that I already do. Then I would like to do that in service. So whom should I join?

The government also clearly wants something from me (I am bombarded with letters from various government institutions, you too?), so maybe I should just apply for a job at the nation? I actually do exactly what they want from me, but now I usually do it for next to no money, so I don’t mind doing the same work and get normal payment for a change.

Below you can read my application letter in full:

Ministry of Education, Culture and Science February 12, 2020

Attn. Ingrid van Engelshoven, Minister

P.O. Box 16375

2500 BJ The Hague

Regarding: Open Application

Attachments: CV and portfolio

Dear Mrs. Engelshoven,

I would like to apply for a permanent job as an artist in the service of the state. The reason for this is the presentation of the final report of the ‘Regulation of Work’ committee.

I am very motivated to continue my activities and professional practice as a professional artist. In recent years I have done this with great pleasure and success. With my work I inspire people, and I make an appropriate contribution to a healthy reflection on society and our national community. The reactions to my work confirm me in this, and I experience that many share this view with me.

But getting fair compensation for my work as an artist is increasingly an arduous process, which is also very distracting from what I am good at and what I enjoy doing, namely making art. It is increasingly becoming apparent that government funds made available for making art are already exhausted when quartermasters, culture brokers, policy advisers and other organizational elements have finished their work. The actual production of art, and the supply of the consequent value to society, is severely limited by this.

In the statements I read about the final report of the committee ‘Regulation of Work’, I see an opportunity to improve this in a pragmatic way. Since the results of my work mainly provide added value for Dutch society, I would like to apply to you as a performing artist. This seems to me to be the most obvious employer-employee relationship for permanent employment as an artist. Since there are no vacancies in this area, I would like to work with you on this in a creative and innovative way. Hence this open application.

My proposal is that I report directly to you, whereby frequency and content can be determined in mutual consultation. As a return service for a fixed fee, which as a starting point may not have to be more than the statutory minimum wage (undeniably many times less than the usual hiring rates for external personnel from the government), I will be able to continue my activities as an artist and continue to contribute positively to depolarization, inspiration, reflectivity, etc.

For an overview of my recent work, I would like to refer you to my website, www.makefactory.nl

My application is also in line with a previous appeal by Mrs. Jet Bussemaker, formerly Minister of Education, Culture and Science, who argued that artists should receive reasonable compensation for their work.

I would like to be invited by you to explain this orally, and to discuss the possibilities and form of a possible employment contract with you.

Thanks for your comment,

Kind regards,

Dienke Groenhout

Well… what will be the answer to that?

To be continued!

Art parasite

|

Research for ArtEZ Art Academy ………….Art, what is it? |

This text is a small part of the research proposal: How can we use art and art education as an alternative for the leading views on what society needs, repectively as an alternative for education that is based on measurability and control. The research involves two major case studies. The second case is the project ‘Art parasite’. Makefactory is developing this together with artist Gigja Reynisdottir. In this case we will research how much or how little context an artwork needs to be understood, and how we can get around the ruling system and still be understood as art. In this case we are designing a mobile artwork that moves around everywhere like an autonomous entity, outside the context. We will travel to all the ‘must-see’ art biënnales uninvitedly and consult the public. |

|

|

MakeFactory on tour 2

Free space

“We have art so that we do not have to be ruined by the truth” Friedrich Nietzsche (Nietzsche, 1966)

With MakeFactory on tour we try to experiment with a traveling Free Space where people can work together on the other sides of the truth and give a concrete shape to that idea.

That’s why we make works that are interactive, and invite the people to operate the work, to enter it or to join.

Together we create cultural projects for social or environmental issues and find a new context and perspective. While traveling we mark the landscape with works of art.

Iran – Strangers in Paradise

Have you ever taken a foreigner or a tourist home with you?

Have you ever invited a stranger to dinner at your house?

And if you haven’t, why not…?

In Iran we are hardly moving forward, the travels are going very slowly and this is only due to the incredible and unstoppable hospitality of the Iranian people. We have to talk and drink tea with everybody!

We arrive in Bandar Abbas with the ferry. We are a bit scared about the strict rules for dress code and we know about the complete ban of alcoholic drinks in the country. But already the second day we find the whiskey and the party people, or rather they find us.

On our way to Shiraz we do some quick shopping for the road and we are ready to make the travel. But then we hear a strange hissing noise coming from the car. We open the cabin to see where it comes from and within two minutes there is a mechanic jumping to the rescue.

While repairing the brake cable, because that’s what is hissing, he calls all of his friends. And in ten minutes we have a party group.

‘You can’t leave now!’, they say after the truck is fixed. ‘The party is just beginning! We are going to eat and visit a waterfall!’. And so we do. We climb a mountain and visit a waterfall, smoke a water pipe and instruct the Iranians to pick up their trash after a picnic in nature. Because everyone seems to love nature and it is a true pleasure to see people enjoying it so much! (although most of them don’t pick up their mess.)

Further along the travels we meet this family entirely dressed in black. Their clothing scared us at first, because we thought they were of a very conservative branch of religion or something, but it turned out their grandfather had died three days before and the whole family was at home for the funeral. The mourning was apparently no reason for them to leave us standing by the road and we were invited to share the meals that were left over from the huge funeral gathering.

Everything in Iran is beautiful, from the tiniest shop to the biggest mountain.

The details! Like the windows with round corners and the cars that look like they are some unknown make from the seventies. Sometimes it feels like we are walking in a film set, so carefully taken care of all the things look.

People must love quality.

The delicious drinks that are served everywhere make you immediately forget about the absence of alcohol and make you realize how poor the drinks are if alcohol is present. Here we are talking rose lemonade with some interesting foam on top and real dried rosebuds, or orange blossom with golden seeds floating in it that whirl in your drink as you stir. Mint lemonade in copper mugs and big glasses of blueberry lemonade with frog eyes, as the kids call it, but that are actually chia seeds. There are walnuts and dried fruits everywhere, and people offer you food and drinks wherever you go.

The best gift was a set of three cucumbers handed through the car window from two boys on a motorcycle while driving!

As we drive through this beautiful country with its wonderful people we fully enjoy the travels, and slowly the critical progressive people that the country holds are being shown. A cup of coffee along the road where an old man asks us to take of the ugly head scarfs when he wants to take a picture, a girl in the drugstore starts explaining why supplies are missing but it ends up in an interesting talk, a stranger on a parking lot spontaneously starts to talk about America and comes up with the idea to invite Trump over incognito to make him experience and enjoy Iran’s hospitality.

And so we slowly reach Tehran.

The Art-scene in Tehran

Staying around in Iran for two or three months is regrettably no option because we need to be in Belgrade in the beginning of August and because shipping the mobile making space took much longer then we expected. So we decide to explore the art scene of Tehran as thorough as possible. Our pick for the hostel is luckily bull’s eye. We meet the first night with a young woman, who is working as a poet and involved in theatre.

She recommends us to do a gallery hopping tour on Friday.

She explains us all about the committee of the government that decides on the content of art works that are being presented in public. They will visit for example a theatre play announced for the obligatory control visit on content. After permission is given to show the piece in public, it is usually changed in to the more critical version of the group’s real story they want to tell. And that is then actually shown to the public.

We discuss a hypothetical performance that came up in my mind and if it would be possible to show such a thing in Tehran. The idea was, to make a giant chador which can be worn by a group of at least 50 women and that looks like a moving sea with in the top parts the 100 wholes for the eyes that allow vision. Would it be possible to do this on the street?

She says there are plenty of critical private art galleries that would have no trouble showing this kind of content within their walls where there is no control, but such a performance would only be most effective on the street. On the streets it would be unthinkable she says, the government would be highly offended and break up the performance.

She tells us about the 30 woman that were arrested 2 or 3 years ago because the stood on top of an electricity point and hung their veils on a stick and held them in front of them.

Nobody exactly knows what happened to them and if they are still imprisoned.

Despite the very critical population and the government seemingly being sloppy with control, the rules are not to be joked with!

She explains that the revolution is now of a more silent kind and regarding the veil: it is coming down slowly and it is moving more and more to the back of the head. Sometimes it only hangs on the last tip of a pony tail.

In the artworks you should always look for an underlying meaning. There is a message underneath every simple looking drawing. This secretive atmosphere causes a very strong sense of togetherness amongst the people we realize.

As I meet with the tour guide the next day I explain her that I am mostly interested in speaking with artists. So for the gallery tour she arranges also a studio visit.

Painting hidden in the office of the gallery.

After we visit not less the three exhibition openings (!) we visit an artist’s studio. (As he is taking the picture he is not in it himself.)

The studio is situated on a square that used to be the prison for political prisoners. The four watchtowers on the corners of the square are still there.

He shares the studio with his friend and together they also provide cyclists with tools to repair their bikes. And by doing this so they independently try to promote cycling in Tehran.

His main skills are in ceramics. His vases look like they are parts of a body. Vital organs that keep people alive but then made of the essential basic material of the planet: soil. In our language the name of our planet and soil are the same word: earth or aarde in Dutch. He shows us also a column that he made, consisting of earth layers but hidden in the layers are also plastic parts and waste of people that is now covering our planet and that probably will be dug up in the future as archeological excavations. An interesting perspective. We share a lot of matching ideas, and hope to be able to stay in touch.

Iran has especially made us realize how important it is to always be friendly to people. Also, or maybe specially the ones you don’t know yet. It is not an effort, it is a promise to a possible adventure. And it will mostly bring you energy, not cost you energy.

After Iran we try to hurry towards Belgrade to pick up our oldest son who flew home from Tanzania, and three friends that are joining us for the last leg home. We pass Armenia and Georgia and made a wonderful trip home through Europe, with beach in Greece, art in Belgrade and Novi Sad (cultural capital of Europe in 2021), peppermint coffee in Budapest, pie eating in Vienna, and Raststättes in Germany.

And no we are back to home base.

Back to life back to reality…

Dubai – Babylon versus Rapunsel

Dubai came on our route because of the shipment of our truck. Luckily a close friend of us, Boba, is living there and working as an architect. Otherwise the Dubaian life is unaffordable. Boba invited MakeFactory to do a Friday afternoon design talk about our projects at the architectural Bureau Perkins and Will.

After the talk we met with some lovely people whom we later that week had an interesting dinner with including a parrot landing on Juli’s head!

We stayed in Dubai for two hot weeks and met with some very nice people in the art scene and fashion. But it doesn’t go unnoticeable that they are all coming from somewhere else. Sudan, Iraq, Serbia, Philippines, Kenya, Canada, Morocco. Just to name a few countries where the people that we met with came from.

It isn’t surprising since 10% of the population of Dubai is Emirati, and the other 90 % are foreigners doing the enormous amount of work to keep the theater of Dubai running.

Because that is what it looks like to us: a theater. On stage the enormous towers, the acclimatized Starbucks, the shopping malls, the metro swiftly passing high over it all and under, the 13 lane highways. Because Dubai is not for walking, it is designed for cars.

There are hardly any people on the streets. Everyone is inside. If you need to take a bus, for some reason (which rarely occurs), the stops where you wait for one are also air-conditioned. When we were in Dubai it was Ramadan. No eating in public spaces. “Everyone is out” says Boba, “they are all on holiday”. By ‘everyone’ he means the Emirati. “We stay here to work” he continues. He works in a higher range job but backstage are the workers that keep the show going. Organized and separated in all gradations of payment and education level. The poorer ones with uninteresting jobs stay in worker areas where they are brought to, and being picked up from, in the typical white busses for group transportation. The richer ones live in the huge apartment buildings in town. But all of them are unable to built up any of the same rights that the Emirati have. You can’t save up, you can’t go with pension and you can never become an Emirati. Sooner or later you are going to have to leave. Old people are hardly seen.

The people here seem to be mainly occupied by building higher and more impressive. Anything they don’t have can be bought. Later on we see some Emirati woman shopping in Dubai mall. They are covered in black. But the black robes they are wearing are made of luxurious materials, fine fabrics with small figures embroidered on them, high heels under them, and much make up on the faces, but nevertheless, entirely black.

Why shop at Gucci or Prada only to cover it up? Well, the expensive clothes are hidden under the robes just to be shown indoors to other women.

The men are dressed in white robes. The richer ones or the ones with higher status wear a small white scarf with black ribbons around the head, and the others wear the Arab scarf folded in a specific way. Money can buy many things, but in contrast to what many people believe, it can’t buy freedom.

Maybe this play was not called New Babylon maybe it was called Rapunsel since one of the daughters of the sitting emir was fed-up with her golden prison. In her golden cage she had everything that she could want to have, she could walk her tiger on the beach (they seriously do, check Instagram), she could buy the most expensive dresses and eat the most delicious foods, but she did not have her freedom. She decided to leave Dubai and carefully planned her escape with the help of a former French spy and her martial arts teacher and an escape boat.

Regrettably she was caught by the Dubaian commando’s of her father’s rulership. She was captured and never heard of since.

Just now as we have arrived to Iran we hear of the escape of one of the Emirs wives (yes he has many, and he has 23 children), who got scared about details she heard about the captured daughter. She fled to Kensington England and asked for asylum and is pursuing a divorce from there. Towards foreigners and workers the Emirati government is tolerant. No dress code and you can buy alcohol but only according to you wages. The more you earn the more you can buy. But clearly human rights are being violated and the world is looking away. Because Dubai has money and because the humans in this scenario are women, not men.

Although we sense the strict rules that don’t apply to us, and we experience the hierarchy that is felt when you’re dealing with a sheikh, we do enjoy the life in oblivion that everyone is living here. The beautiful lights at night, the musical fountain in Dubai mall, the mall itself and shopping at the very expensive fashion designers shops and touching the wonderful fabrics. It feels like an eternal Christmas, but then in summer. The shining pool on the roof, the carefully manicured grass next to the white beach and the clean turquoise sea. You’ re in the matrix and you don’t know any better.

The people who are from everywhere and who are always hungry for stories are really interesting to talk with. To hear the many stories of their homes and cultures.

The dinner trap

One day we get a phone call of a certain man who has seen on Facebook and Instagram that we are in Dubai with our MakeFactory truck. Would we maybe be interested in a cultural dinner with one of the members of the royal family?

Well yes of course! We feel proud, we have an interesting story after all and if the sheikh would like to hear about it, he must be a nice man who loves art and travel!

The dinner is at ten and we will be picked up. Ten?!! That is when we usually go to sleep, but of course it is Ramadan and everyone sleeps during the day (the Emirati that is, the rest works) and starts to live around 8 at night when its cooled of and when they are allowed to eat again. But even the boys decide they can’t miss this chance to visit a real palace! Maybe there will be tigers on the beach.

We immediately call Boba: “This is huge” he exclaims, “I’m coming too!”.

As soon as he comes home from work a whole Cinderella scene starts: what to wear??!! Everybody is walking like a headless chicken through the apartment. Boba and Oscar are off to the hairdressers and Ate is buying nail polish at the mall.

Finally we are presentable and nervous, when this guy shows up and picks us up in a big SUV. We are swiftly driven to the palace and brought to a sort of reception salon.

Hmmmm…. what a strange atmosphere…. is this a palace?

Scruffy chairs are placed along all the walls, piles of books and cardboard boxes in the corners. The sheikh who’s receiving us is playing chess with an old fat guy, and only shortly nods. What is this?

A group of people (from Zimbabwe we hear), also nicely dressed just like us, are being walked in by a Pilipino guy in the Emirati folklore white robe. He sits them in a circle behind us and starts to lecture them about Islam. Oh no! They silently nod politely and reply very little. When it is dinnertime we are brought to a huge table, where the group of unshaved and chubby looking men in the white dresses already occupy half of the table.

The sheikh sits across from them and we are sitting on his right side. The table is loaded, with meat mostly. But when we say that two of the kids don’t eat meat the kitchen quickly makes a pizza. Sake falls asleep behind Dienke on the fluffy huge chairs that we sit on. The sheikh is talking about his shooting championships in the Olympics. It is quiet amusing we must admit but he never once even asks a question about our project. Oscar tries to bring it to his attention, but he doesn’t seem to care. After dinner, when it is already midnight, we are summoned back into the sitting salon. While we wait for the sheikh to come and have his personal talk with us we are looking at some photo albums full of pictures of men that caught a huge white shark. Sitting on the shark, holding the shark, lying next to the shark. Poor shark.

And then the lecture begins, about why the bible contradicts itself and where exactly it contradicts itself, completely affirmed with the corresponding verses, so quickly found that it reveals the sheikhs routine regarding this matter. We do not believe in Islam nor do we believe in Christianity, so the whole talk is completely pointless to us.

Finally at 02.00 we are released. We say something about how it is very late but the sheikh replies with ‘Don’t worry, I don’t mind you keeping me up, I sleep during the day’. We are so amazed by his remark that we almost forget to keep showing a polite face.

Back home we laugh, my god have we been trapped!

Just not to end with this horrid picture here’s two pics we took in the independent studio of some young designers.

The name of a start-up fashion label, and a picture found on a big scrap board for ideas.

Addis Abeba

Our super short unexpected visit to Addis Abeba (simply Addis for its residents) deserves an extra newsletter of its own. So here is an extra addition of the adventures of MakeFactory on tour!

We had to spend a whole extra month in Dar es Salaam to get the truck on the boat to Dubai. It was a Kafkaesque bureaucratic adventure including completely absurd situations that would actually also deserve its own story. Imagine it is 40° C and the humidity is 80%. After a 100 meters walk you are completely soaked in your own sweat. Crowded offices with people waiting hours and hours. The digital age has not yet started in the administration of Tanzania. We need many papers and we need to show up everywhere in person.

Pity we read this message only after I came to the office.

One minute people wait in lines and pay money and do anything to get a small pile of really important papers together, and the next minute the same papers are released files…:

We found this pile in the ports customs office.

But eventually we were able to get the truck on board of a Safmarine/Maersk ship.

Not just that, but we have to genuinely thank Safmarine, since they decided to sponsor our truck shipping to Jebel Ali, the port of Dubai.

We are truly truly grateful for that, because it was going to bankrupt us nearly.

Thank you Safmarine for your braven![]() ess to receive us and listen to our story, and to contribute to our projects!!

ess to receive us and listen to our story, and to contribute to our projects!!

The shipping to Jebel Ali takes 4 weeks. So in the meantime we decided to visit Addis and we were welcomed in the home of Geke and Tamrat. Geke works for an NGO that takes care of refugees and her husband Tamrat is a visual artist.

While walking in Addis and absorbing its very rich culture a new project was quickly born. Three weeks seems a long time to just visit and not make anything… Plus an inviting and inspiring environment like Tamrat’s studio, Guramayne Art Center, where the studio is located, and Geke’s stories about her work with displaced people gave lots of food for thought.

Also we noticed while we were visiting Merkato, a busy market place in Addis, that we had received yet another name here in Ethiopia: here we are ferengi’s.

Visiting Africa, we were given many names: Toubab (in Senegal), Mzungu (in Zambia and Tanzania), Ferengi (in Ethiopia), etc.

Although we are new in this continent and we have never been here before, we have already many names.

I guess when people call us these names they are referring to something that could be defined as ‘my people’. I am not sure who these people are or where they come from and I do not feel a certain connection to ‘my people’, but still I seem to be categorized amongst them.

People know and recognize each other’s patterns. In your hometown you can warn the police if you see something suspicious. If you do not recognize someone’s movements and it is new to you, you will try to find something that you recognize. Something to hang on to. This is where I am a ferengi, a mzungu, a toubab and I will be fitted in the mold of the ferengi that people have made for the ferengi’s.

What do they do, how do they move?

But what if I walk the streets and no one can place me? What if people cannot see any context for me? And no one recognizes any patterns in which I move or behave?

I decided to make a suit, that will make me unrecognizable, and to combine it with learning some traditional skills, like braiding with bamboo and banana leaf and palm tree leaf.

If I am a walking gobble ball, a fluffy tree, how will they call me? What if there is no context for me yet…?

Here you see the work in progress: Genet teaching us braiding with grass.

Genet’s neighbor braids with bamboo:

So within a week we finished the suit, and we planned to make a street performance with it, to find out what would happen.

On the Monday before the performance MakeFactory was invited to do a presentation at Guramayne Art Center followed by a discussion. We talked about the suit and there was one man very interested who asked us how we would bring the suit home? We told him we couldn’t take it home and that it would have to stay in Ethiopia.

When asking him if he wanted to have it, he eagerly nodded ‘yes’. So we told him: ‘then it’s yours’.

This man turned out to be the director of the National Theatre! So our performance route was now decided. Destination: National Theatre.

Walking in the suit was an interesting experience. At a certain moment I started to feel lonely. People where making a lot of contact with me, but it was not really me, because I could not see them. They where just talking to my outside. In the same time I also felt a sort of safe, because they could not see me. I didn’t have to smile or reply to anyone.

Still after some time I noticed that I wanted to reveal myself and make real contact and answer to people who talked to me.

As I walked longer and longer I also understood that it was not me who was showing anything. By all the remarks people made I started to see how they revealed themselves to me. They where the ones showing themselves, they where the ones doing the performance, I was not showing anything.

Some people said it was beautiful, others quickly made a cross on their chest, and some laughed and liked it, and some people said it could make a lot of banana leaf bread.

Practicality, beauty, joy, fear, misunderstanding was all that the suit showed in people.

I guess even if people do not recognize anything, they create their own individual context immediately.

As we arrived at the theatre we surprised the director, cause we did not tell him we were coming. He was very happily surprised and put on the suit directly, and he disappeared into the theatre with it. The suit couldn’t have a better destination! We are currently making a video of the performance that will appear online shortly.

Lots of thanks to all the great people who helped us with this project!

Geke, Tamrat, Teji, Genet, Yero, Manyazewal, Dymph and many others!!

Dar es Salaam – Nafasi Art Space

MakeFactory is now a good 5 months on the road with the project ‘mobile making space’ in which we create cultural movement on the spot, for and with the environment. With our traveling meeting- and working space, we collaborate with local cultural organizations and invite the people to join. So far we have been able to do quiet well in accordance with our values.

But our travels started also with a quest to create or find a sort of free space. A space in which we, and the people that we work together with, can make our own rules.

A place where the usual rules of society don’t apply. A place where we do not have to be limited by expectations, politics or money. This quest is one of the reasons we try to never involve money in our projects and try as much as we can to exchange services rather then to pay or get paid for them. This way we hope to create and share an alternative view on society with an artistic perspective instead of looking with an economical or political perspective which are much more dominant in society.

Autonomous playfield. Warning! Any similarity with the truth is purely coincidental

There are circumstances that complicate that, like inequality, or bureaucracy. Yes, almost we would not have had any project in Zambia because of bureaucracy but luckily we were able to create a work around. Here at Nafasi where we have been working now for almost two months, the quest is made a bit easier again.

This is already a free space of its own. It is a messy colorful terrain filled with workspaces, ateliers, documentary makers, sculptors, a dancing school and lots of smaller creative businesses. In the center are a bar and a kitchen that provides lunch every day, and it is the place where many conversations, discussions and collaborations arise. Everyone greets each other and not many things surprise the people working here.

In this place other rules are at work then the traditional once from the society outside. Boys dance ballet, and girls welder large sculptures. There are single parent families and people without religion. Many things that are accepted here are not quite accepted outside the gates. And that is why also many people like to hang out here that do not work as artists, but that do feel at home here.

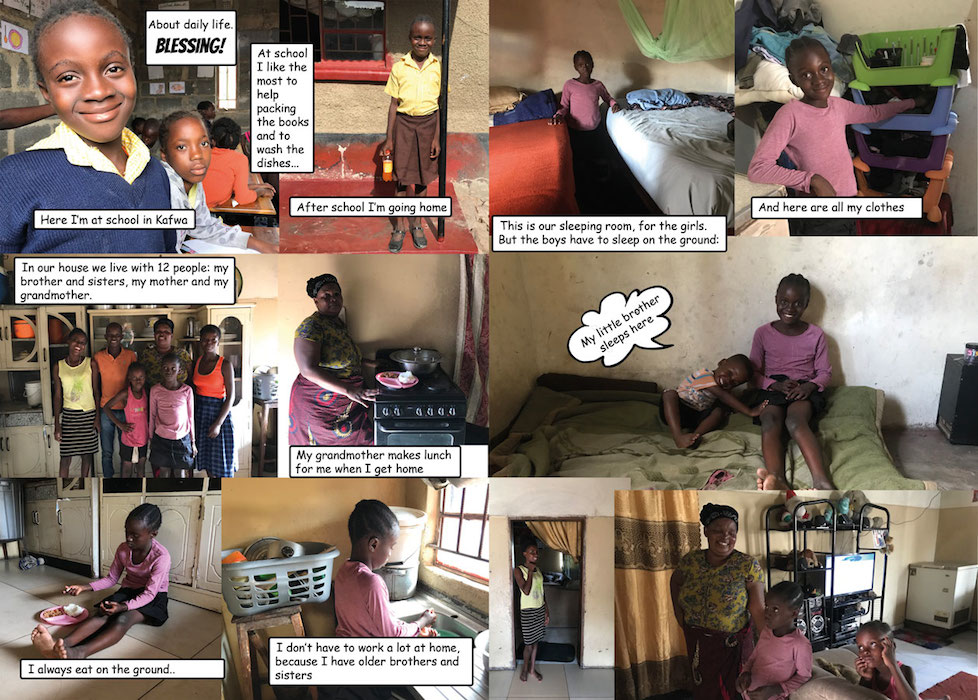

Zambia’s project was truly amazing and we are proud of it, but it was also very intensive. It was intensive to serve everyone’s needs and wishes as good as we could, but also to not share our opinion when habits or traditions are at work that are incomprehensible to us. A ten-year-old girl that runs an entire housekeeping after coming home from school, while her 20-year-old brother is at home without a job, is an example of that. The girl we talk about wanted to show her daily life in the book we made (view the book here). And we only show it, we do not comment on it.

But here at Nafasi there is another discussion alive, here it is about art. Everyone already agrees that the rules in the art world are different then the ones in the outside world, although they do sometimes seep in from under the gate….

Nafasi was already planning a big exhibition based on the question ‘How did we get here?’. MakeFactory was asked to give our artistic answer to that and to create a work for the show.

Our personal travels and metamorphoses have everything to do with our actual travels of course. We wanted to make an answer to the question as a group and not from the perspective of one person. So we looked at what applies to all of us. We chose to approach the question from our new and changed view about ‘home’. What does ‘home’ consist of now that our home changes all the time?

It is no longer connected to the objects or the physical house that normally surrounds us every day. Although objects can make us feel at home somewhere they now resemble another quality to us. They are much more replaceable and we look at them mostly as useful items and not as personal items.

All together we created the installation ‘floating home’. A collection of single, seemingly fallen apart, objects, that you could normally find in a house but that seem to have little meaning. In between and around them seeps a blue liquid that is leaking from several objects and that connects the single elements together.

Joseph, a choreographer who has studied at Muda Africa, which is the dancing school here at the terrain, made a performance together with dancer Boni, especially for our installation. The performance was shown at the opening of the exhibition and the festival ‘Asili Ni Tamu’ that took place on the 30st of March. During the performance, Boni washed his face with the blue paint that was streaming from the paper sink, after which he shook hands with people from the public with his paint-covered hands.

The blue paint symbolized the connection to the people. And it is that connection that can create for us a feeling of being at home while we are traveling.

We expected many people to refuse to shake hands with Boni, but that didn’t happen at all. Everyone except one man took his hand. And after the performance had finished the people with blue hands started shaking each other’s hands as well.

And while we were all creating paper objects together, there was also a cat being adopted, a master class given at UDSM, University of Dar es Salaam, in cooperation with artist Safina Kimbokota, a chap chap given together with Tanzanian FilmLab and a tree house built by Mees and Sake. Yes, we worked a lot!

Although we got to know the art scene pretty well and we could of course call Nafasi a community, we have to admit that our ‘floating home’ was also standing on a floating island. We know little about Tanzania’s other communities besides the art community.

We do know however that the art community is discussing one very dominant issue: Tanzania’s identity. And this is the issue with which the rules from outside seep in from underneath the gate. It seems as if everyone is very much looking for it, and most artists seem to think that Tanzania is currently in an identity crisis. Swahili has united many tribes but it may also have caused the loss of some identities.

Unification is maybe always causing identities to become lost or forgotten. It is a complicated issue that feeds discussion but also allegations and prejudices. But luckily it also results in artworks, as the exhibition ‘How did we get here?’ shows.

Home away from home van Mees en Sake

In the meantime, we want to let our floating home drift of slowly towards new locations. But it isn’t that easy. And while we spent long days at home waiting for sudden action that needs to be taken, interspersed by days of visiting the hot city to find new shoes for Sake, it is slowly getting closer and closer to the date that the ship is leaving and the visa for Tanzania are ending. Will we make it at all to India?

After two weeks of visiting offices, doing paperwork, and a visit to the tax office (our road tax turns out to be expired) it turns out that shipping to India is going to be to expensive and it will take to long. We would have to wait in Mumbai more than a month for the arrival of the Magirus. Next to that, it turns out after a bit of research that there are only to ways leading out of India over land. One is going through Pakistan. From Pakistan we would have to take the only border crossing with Iran to be able to reach Europe. It is possible, but only while you are being escorted by a heavily armed anti-terrorism swat. Plus the border is all the way up north, so it means that we would have to cross the longest distance through Pakistan. It’s not a good plan with young kids.

The other route is very appealing: via Nepal to Tibet, up through China to Mongolia and then left through Kazakhstan, and Russia to Europa. Fantastic! Distance: 15,000 km.

After a bit of calculating, the Magirus maybe can do a maximum of 40 or 50 km per hour, and we don’t want to drive more then 4 hours a day, we conclude that it will take us three months and then we can not stop for even a single day. Petty!

So a change of plan: we ship the Magirus directly to Iran, drive through Armenia, Georgia and Turkey back to the Netherlands. The good news is, we have a very special and interesting contact in Iran. A girl who is a graphic designer in Iran’s art-scene in which almost all artistic expressions need to be done underground.

So the whole crew is a bit sad about India, but we do have the time now to do a very interesting project in Iran.

Garden Stories – the book

Garden Stories – the book

View here the entire book:

Village visit Pentauke, Zambia

We already discussed with Grace (Barefeet’s director) the first meeting that a village visit would be essential to find out about Zambia’s rural culture and also to experiment on how the truck could function as a cultural meeting space. In the last weekend we plan to go. It is a special visit. Grace’s mother comes from the village we are going to visit and she has not been there for more than ten years. Also Grace’s brother and sister join, 6 children, and John, Barefeet actor, husband of Grace and our friend.

The Magirus between the huts.

The village is truly beautiful. The huts are round and made of the typical red clay out of which the Zambian soil consist. If for some reason the village would have to be abandoned by its 700 inhabitants, it would be perfectly absorbed by nature.

There is no plastic to be found. And the rare plastic items that are present are carefully reused. The large 5 liter water bottle that held our drinking water contains a homebrewed maize beverage the next day.

Cleaning pumpkin leaves.

We arrive late in the evening in the village. Although everyone has already noted the truck, we are only calmly being approached the next morning around ten. “Hello, are you looking for something?”, says an older gentleman. We explain that we are visiting the sister of Dorothy but we forgot her name and since Dorothy hasn’t been in the village for more than ten years, the man does not know who we are talking about. But then we remember her daughter’s name, it’s Maragareth. “Ohwohw” he answers. Which means something like okay. With his hands on his back the gentleman is quietly watching who is coming out of the truck.

If we are all together on Rose’s courtyard, (because Rose is her name) to drink tea and eat maize porridge for breakfast, a group of children gathers on the side of the yard.

All the grownups are working on the land untill around 11:00 and then return for lunch and start the other work that needs to be done.

So only around 12:00 or 13:00 the few small shops open that sell things that are difficult to make by hand, like washing powder. They also sell some candy and chips and soda’s.

The kids are peaking at us curiously, but if we try to approach them, the run like shy little creatures. In our group is also David, a three year old toddler, who is the son of Grace’s brother. David enjoys the children running away! He pretends to be a monster and chases them away.

For the kids from Lusaka the village life is just as new and different as it is to us.

In the afternoon many people are passing by to shake hands and say hello. Some of them are curious about us, and ask us what we think about Zambia, while others come to speak to Dorothy, who they still know from the past. At dawn something needs to be picked up from the Magirus. When we arrive, we find a group of kids gathered around the truck. We show them an old trick, looking like the top part of your thumb comes off. The kids jaws drop, as the scarely watch the trick.

We carry some thumbs with magic lights with us. We perform a spontaneous show. The kids love it, over and over they want to see the tricks. If we become tired of playing the tricks over and over, Rose summons them to go home. And well-behaved the kids turn around and wave goodbye.

Village life is calm. People are occupied with the daily necessities, and maybe with planning activities concerning the seasons. There’s no ambition or pressure to reach a certain goal.

Grace tells us that a few family members have tried to live with her in Lusaka. They had the chance to study and build up a life, but eventually decided to go back to the village because they couldn’t adapt to the city lifestyle. After sharing the slowly village lifestyle for two days, and enjoying the scurrying pigs and chickens, we can relate to their decision.

But still, after some time, you start to wonder if it wouldn’t be possible to provide the shoo with an actual toilet seat, the same system would remain, but it would be more comfortable. And a shower, without any water piping, is not difficult to realize. It’s easier than washing up in a bucket. And in the kitchen you could easily make a counter, with a small pump, so you don’t have to scoop up water from a bucket. And maybe the windows…. and the…., and so you can go on and on, and before you know it, you’re have something that people call development. Something that results in wanting more. It can always be better, improved, and innovated and eventually you have urbanisation, and cities that make huge pollution.

Luckily it was just a daydream in a village somewhere in Zambia……

Garden Compound, Lusaka, Zambia

Meanwhile in the Netherlands, the high school kids are protesting against climate change and their parents are posting the whole thing proudly on Facebook and we are having a close look around us in Zambia, and we realize ourselves how much this is a problem of the richer countries in the world. Fingers are being pointed at third world countries sometimes when it comes to plastic pollution but in Zambia we can be sure that a carbon footprint is only a fraction of a Dutch one.

Right now we are working on a photo special about climate neutral production of goods here in Zambia. Soon you will find this on the website.

After meeting the fantastic team of Barefeet theatre, we decide that the best idea for a project is to work with a group of teens in Garden Compound.

Next to the work Barefeet does to get street kids back into the community, they also work on prevention. Garden Compound is one of the locations where kids in trouble are at risk of choosing a life on the streets.

Garden Compound is a ‘favela’ in the heart of Lusaka.

The people that live here are living a life comparable to a village life. There is no water pipe to the separate houses. Neither sewage. One shares a public toilet with a group of houses, and collects water from a shared pump or tap. A kitchen is a collection of water buckets and containers keeping the clean and the dirty dishes.

Cooking happens on a small coal stove on which you cook Nyshima, a thick maize lump with which you pick up the other foods, usually fried pumpkin leaf and meat or fish.

No cutlery is being used. The main difference compared to a village life is the absence of plastics and city dirt in the village. The village is a lot cleaner.

The houses are small. It is no exception if people sleep with six on one big matrass behind a curtain that divides the room. Now that it is the rainy season it can happen a few times a day that people have to run inside to stay dry. And then there is little place to take shelter.

On the edge of the neighbourhood is a library. One of the very few indoor public locations to go to when it rains.

So when a pour-down starts many kids go there. There are quite some books in the library but they are being used by many many children. Around 300 children visit the library every day.

The books are all in English. In Zambia 7 languages have been appointed to be an official language of the 70 that are being spoken. English is the first national language but in Lusaka most people speak Bemba or Nyanja. The many languages in the country are one of the reasons that school books are being made in English. The content of the lesson books has been mostly adjusted to a Zambian life, but the storybooks have not. They tell stories about English lives. Lives that a Zambian child may not relate to at all. Some of the books even have a truly colonial content.

In Zambia, TV channels also show a lot of foreign content. Images of lives far away and not representing an average Zambian life at all.

As we arrive at Barefeet and meet with the team some of the team members are busy acting for a new soap series.

A new Zambian channel has just been launched: “Zambezi Magic”. They want to show only Zambian content. Suddenly I realize how much we are being bombarded also in the Netherlands by American content on our TV. Netflix, Nickelodeon, Disney, Cartoon Network and so on. Wouldn’t it be great if we got to see Zambian soaps or Indian and Chinese instead? Why not?

We are starting to believe American life is the same as our culture, but it is not, we have just been adapting to it slowly without noticing.

The TV-crew at work:

After seeing the books at the library and the huge number of children that have to share them, we come up with the idea of making a book. A book that is especially about the life in Garden Compound. That tells the stories of local heroes and local history. We are sure that will inspire kids and convince them that their lives are interesting to read about.

Barefeet has a Children’s Council. A group of youths who are trained to educate their peers about life topics such as aids, early pregnancies and domestic violence.

They do this by using storytelling, workshops and theatre practice.

Three students from this group volunteer to become our solid research team. Next to that we have an arts and drawing team. Those are the students who meet every week at the library for art classes. And we have a team of flexible people that drops in whenever they can.

From our Magirus truck we start to work. Our Mobile Working Space in full action!

As a micro cultural centre for the many children who come to draw every day and as a shag from which the team conspires our plans.

The team on its way collecting stories.

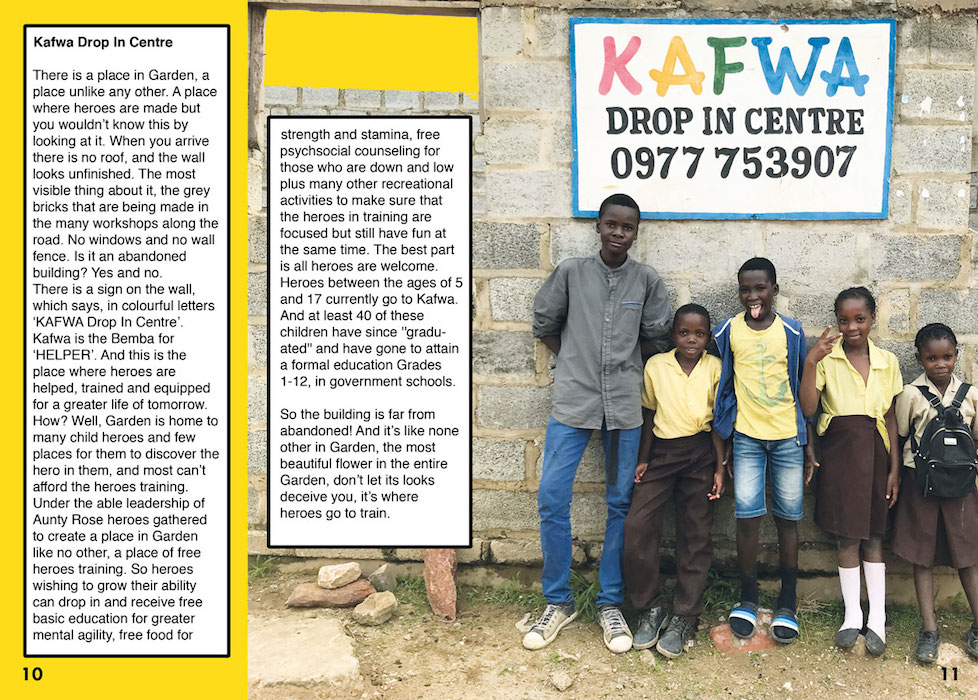

For three weeks we intensively research the neighbourhood to harvest urban myths and stories. We park our Mobile Making Space everyday in front of Kafwa, an independent school. Because we operate from the same location all the people know us after a few days, and when the Magirus turns around the corner the children already start running towards us to come and tell us stories or to make drawings. Pencils and especially coloured pencils are not something that people own for themselves.

It is a complicated job to take care that all the enthusiastic kids get their turn. But luckily this is one of the Children’s Council’s specialties.

We discover very divergent stories about Garden Compound. Dramatic ones, humoristic ones, remarkable ones, and also we discover that Garden Compound’s history shows a very self-sustaining and independent soul. An almost anarchistic atmosphere. The prove is shown in the existence of the many self set up initiatives. Kafwa itself is an example. A school providing holistic education that was established especially to help out kids who are not accepted in a governmental school, or who can’t afford one. Because in Zambia school is not mandatory, but just a right. That means that if parents can’t afford to have their children follow education, they are allowed to keep them at home.

Children also begin much later or sometimes earlier with school, depending on the parents’ working situation. So sometimes kids that are in the same grade can differ four years in age.

The kids that can go to school are very motivated. On one day one of the teachers of Kafwa went to his other job (he was also a part-time electrician) and left his class without a teacher. We took over his job and started teaching them first about the Netherlands, then we taught them some French on their request, and eventually some Japanese. Everything was written down and listened to carefully!

After four weeks of research, drawing, collecting, writing and designing, we have to get the book printed pronto! Because the next day we have agreed to present the book at Kafwa Drop-Inn Centre and invited a lot of people. After sitting at the print shop the whole day and watching the process closely, the book is finished!

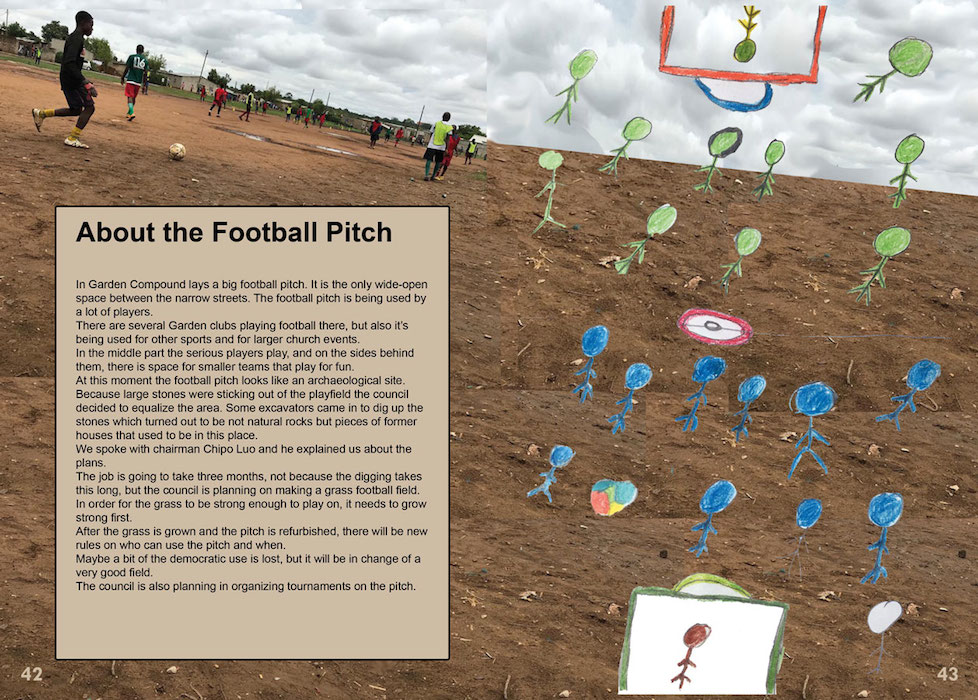

The result is a very colourful magazine-like book with a hand-drawn map by Juma, drawings of all the kids in the neighbourhood, stories of local heroes and drama’s, and urban legends of crocodiles that seem to live in the sewage. The last story appears to be true in the second workweek, because on one night we are bombarded with messages from the team that a real big crocodile was caught!

Barefeet’s dance and acrobatics team is present to support the presentation. As soon as the drummers begin to play the people are streaming into the courtyard. John and Thomas, the acrobats, provoke a lot of cheering and clapping. Traditional dances are being performed and all the people join in the singing. If we show the crowd the book for the first time all the kids are cheering and applauding as soon as they recognise themselves, or the work they made. We show them the pages walking past around the circle and holding up the pages.

The kids are proud, the team that we worked with so closely is happy. They enjoyed discovering things about their neighbourhood. We have learned a lot too. About globalization from another perspective, about formalities and informalities, and about how art works between those things.

The weekend before we leave is busy. On Thursday the Barefeet team needs to do a performance in Ndola. An American organization that has set up a school there has brought Barefeeet to America before, and now they are keeping their promise to do a performance at the school in return. Mees and Sake appear in the show!

Regrettably our driver needs to drive almost 16 hours on that day, while the next day the MakeFactory village visit is planned. Read more about the village visit here.

And finaly dear people, and especially all of our sponsors who have contributed to keep our mobile making space rolling, and who are not on Facebook, we owed you this picture!

If you also want your name on the Magirus, it is still possible.

Thanks!

Outreach

Today we had a very interesting and impressive program. Together with two faciliators from Barefeet Theatre we went on an outreach.

Outreach is one of Barefeets core activities. One or two facilitators visit places in town where a lot of streetkids hang out, and get in touch with them. They chat about all kind of things, about life, possibilities, opportunities. Today, they also brought some clothing for the kids with them.

The facilitators know the street life very well; one of them actually lived on the street for some years, before accepting a place in an shelter. Now he’s a grown up, and working for Barefeet Theatre.

By just giving the kids attention, listening to their stories, and making them feel they’re also worth it, the facilitators try to empower the children and rethink their life, to vision their life in another way.

It was very impressive to us because we saw a lot of very sweet kids, but a lot of them completely drugged, ruining their bodies ánd their life sniffing on plastic bottles.

On the other hand, we experienced the social structure, the community, and the protection of the group they live in. They also have a daily routine, just like everybody else: washing their clothes, getting water, begging for money on the streets, social activities with each other.

But without feeling the urgency to change anything from within themselves, they’re stuck to their bottle. And it is exactly this what Barefeet and MakeFactory are working on: making these kids see other possibilities as well.

Next week MakeFactory will start with a new project in Lubuto Library in Lusaka’s Garden compound. With kids from the compound, also vulnerable, but not as on the edge as the kids we’ve seen today. We’re very much looking forward to this project! We’ll keep you updated.

Zambia

At the border it is as if we are suddenly part of some kind of strange performance. We need to pass by 5 different window offices. A friendly old man explains us in which order we need to pass them by. First a body scan needs to be made of everyone. If you have a fever, you can’t pass through. Then migration, that’s where you buy a visum. Now we have to get the Magirus to pass. Which means one window for insurance, one window for road tax, and one for clearance. At every window we buy a beautiful looking paper with shiny bits, colorful stamps and watermarks. When we are finally able to proceed it is already 14:00h, we won’t make it to Livingstone.

As if to proof that the papers purchased at the border are a serious necessity, we are being stopped every 30 kilometers or so to show one of our dignified papers.

But besides that everyone of us feels the lighter atmosphere in the country. Such jolly happiness in Zambia, everyone smiles and greets us. Or is it just our relieve to leave Namibia?

After three days of travel and a visit to the world famous Victoria Falls, or Mosi O Tunya (smoking thunder), we arrive in Lusaka. Our working location, Barefeet Theatre, is an absolute wonderful place. Here people are working on theatre and theatre workshops to create chances for kids that try to leave their life on the streets behind them.

Here a few pictures of the Garden compound, the neighborhood where we’ll work: